Workslop

Great neologism, brilliant argument, sloppy research?

Like many of you, I read the Workslop article in the Harvard Business Review (HBR). The term is banging. It is that rare thing, a brilliant neologism.

“We define workslop as AI generated work content that masquerades as good work, but lacks the substance to meaningfully advance a given task.”

When I read it, I immediately concurred with the findings, in that it reflected my own experiences (confirmation bias is a thing). For instance Linkedin is filled with inane writing that doesn’t say much, but that looks good at first. I read it and then wish I hadn’t.

It’s an excellent riposte to the continuous barrage of “AI is Awesome.” It’s a really well written article, I was especially pleased to see mention of Nicholas Carr, whose work two decades ago influenced my own perspectives on technology’s societal impact. The article provides sensible advice too.

Like many of you, I shared the article widely. It has generated millions of impressions, and it is being quoted and discussed by many commentators and journalists.

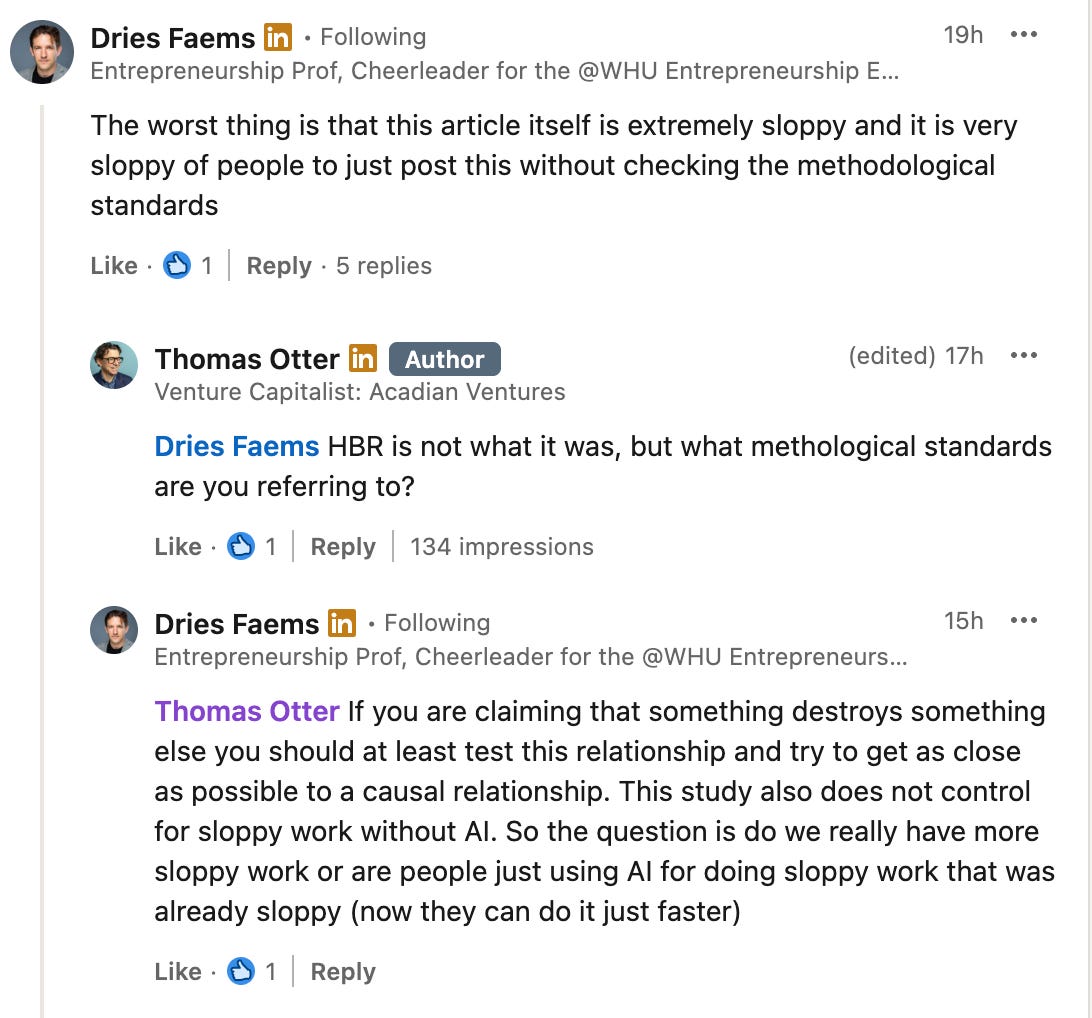

What I didn’t do is pause to assess the methodological robustness of the underlying research. Two of the commentators on my original post did, and I’m grateful for them for doing so. Thanks Dries Faems and Daniel Mühlbauer. You can see the thread here.

The thread continues. I get this spectacularly wrong.

I’m not a research methods guru, whereas as Dries and Daniel are, nevertheless, I’ll have a go at pointing out some concerns. It would be super if other research method experts were to weigh in too. Of course, I’d like the authors to respond too.

It announces causality (workslop destroys productivity) without really testing it. Productivity is notoriously awkward to pin down.

A better title would be “the people that did the survey believe that their productivity is impacted by workslop.” But I guess but this doesn’t make for snappy copy.

Dries expanded in a separate chat.

My main methodological concern here is actually that the authors assume that sloppy work did not exist before AI. My hypothesis would be that a lot of sloppy work has simply shifted from sloppy work without AI to sloppy work with AI. If my hypothesis is correct, the destructive effect of workslop would be much lower than the authors would suggest (it might actually even the reverse because now at least people can do sloppy work faster and more efficiently).

I’m not sure if Dries’s hypothesis is correct, but that’s what research is for, to test out hypothesis.

I make an additional conjecture: AI is destroying the heuristics we have honed for decades to quickly identity sloppy work (poor formatting, spelling errors, no references etc). The result is not necessarily more sloppy work per se, but greater detection difficulty, which raises the cognitive and temporal cost of evaluating quality. We need a new sniff test.

Dries has a point about the methodological weaknesses, but it is a critique that we can level at so much of what we read about AI: Bold and risky leaps from correlation to causality.

A survey that collects people’s opinions can be genuinely useful, and I can gloss over the headline’s presumptiveness of causality. They make some plausible assessments, summarize the perceptions of the survey respondents well, and provide some sensible suggestions to use AI more effectively. It is a provocative hypothesis, but it’s a long way from being proven.

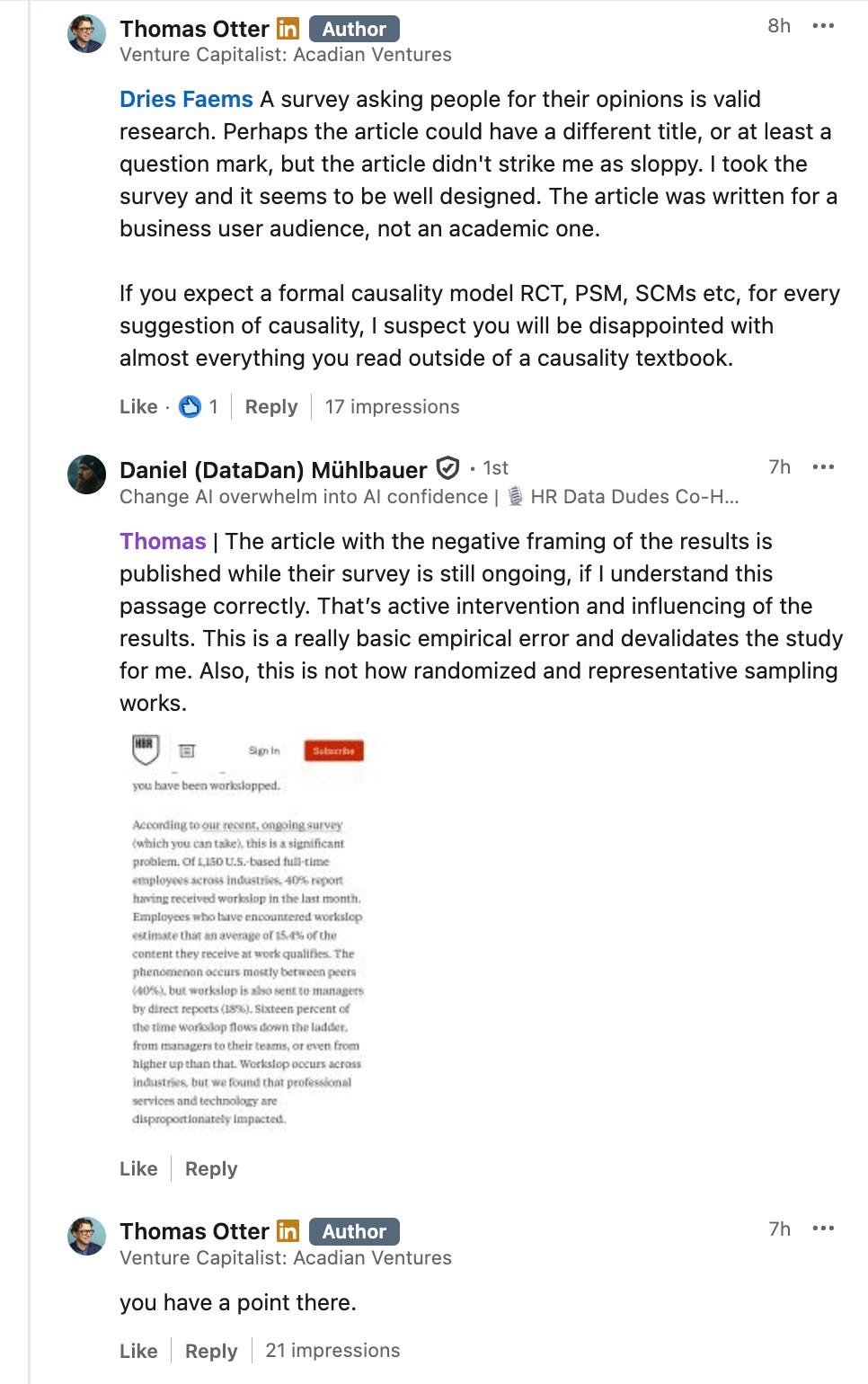

But there is a bigger problem

The bigger problem is that the authors wrote up this article while the research is on-going, and linked to the survey in the paper. This is the research equivalent of leading the witness. It will result in sample contamination and bias: Post-publication contamination in the form of.

Response bias - new participants might be influenced by the published findings

Confirmation bias - people who agree with the findings might be more likely to participate

Priming effects - seeing the results could influence how new participants respond.

As Daniel notes, this devalues the dataset.

I then asked ChatGPT to summarize our concerns in the style of formal peer review. This may in itself be workslop, but I’ll risk it.

The study reported in HBR exhibits several serious methodological flaws. It assumes that sloppy work is a novel by-product of AI, without establishing a counterfactual baseline to show that sloppiness has increased rather than simply shifted form. The construct itself suffers from drift: what counts as “sloppy work” has changed from surface-level errors to superficially polished but substantively weak AI outputs, undermining measurement validity. Established heuristics for detecting poor work are disrupted, meaning what is observed may be a change in detectability rather than incidence. The reliance on cross-sectional, self-reported survey data further exposes the results to recall bias and overestimation, while the extrapolation of subjective time estimates into aggregate cost figures inflates the claimed impact. Finally, by using the article itself as a recruitment vehicle, the authors contaminate their sample with self-selection and demand effects. These design weaknesses mean the findings are best read as speculative hypotheses rather than credible evidence of AI “destroying productivity.”

So what?

I hear you saying, get off your high horse, Thomas, it’s an HBR article, not a AMA paper, so don’t expect 2/3 of article to discuss methodological limitations etc.

But the research is under the auspices of the Stanford Social Media Lab, so that creates a signalling effect to the typical reader that this scientifically sound stuff. Lots of folks will scan this and think that Harvard and Stanford have validated this work.

It would be have been better if the authors had published an academic peer reviewed paper first, and then written an article summarizing the findings.

I’m not suggesting any nefariousness on the part of the authors, just that the article isn’t methodologically robust as it should be. The article makes a plausible conjecture, it coins a memorable word. It’s flimsy research but brilliant marketing for BetterUp. It has garnered many thousands of “earned media” impressions. Spend a moment on their website, and it becomes clear how the article helps position their product offering.

After I wrote this, I noted that Pivot to AI has a blunter critique.

This brings me to a broader concern: HBR.

15 years ago, HBR was brilliant at taking the best published work of top academics, and turning it into accessible, practical guidance for business leaders, or more often, aspiring business leaders. HBR served as a gateway into the much of the best research.

Today HBR has far too many articles written for or by vendors and consultants. In the search for ever more clicks and shares, its headlines have become bolder, and the content less grounded. At one level it has become a vehicle for product placement. HBR once had an editorial position, not merely an advertorial one. There is too much business and not enough review. I’d suggest we are seeing another neologism at work, Cory Doctorow’s enshittification.

As I usually do, I’ll end with a tune. Bryan Ferry’s version of As Time Goes By. This album is lovely and it serves as a brilliant gateway into the music of the 1940s. Do look up his version of Foolish Things and Miss Otis regrets, and then listen to the originals and many other great covers.

Thank you for pointing this out.

Workslop maybe as well the word of the year, but how they got there, well. As a marketeer I am impressed, though.

Smart 'noodling' and 'deep rabbit-hole curiosity' but with humans instead of GenAI. Which is refreshing for a change. Liked the use of CGPT to summarise your findings.

Love how your mind works Thomas.