On the Forward Deployed Engineer, Product Led Growth and genuine adoption.

A call for moderation, perspective and a dollop of innovation.

Chunks of B2B Venture capital and the associated punditry are now deeply in love with the Forward Deployed Engineer. Smitten. In no time at all, implementation service work has been transformed from an unfortunate evil into this cool new must have hero thing, that solves the AI deployment challenge, charms customers and simultaneously builds or at the very least contributes to product capable of being deployed to multiple customers.

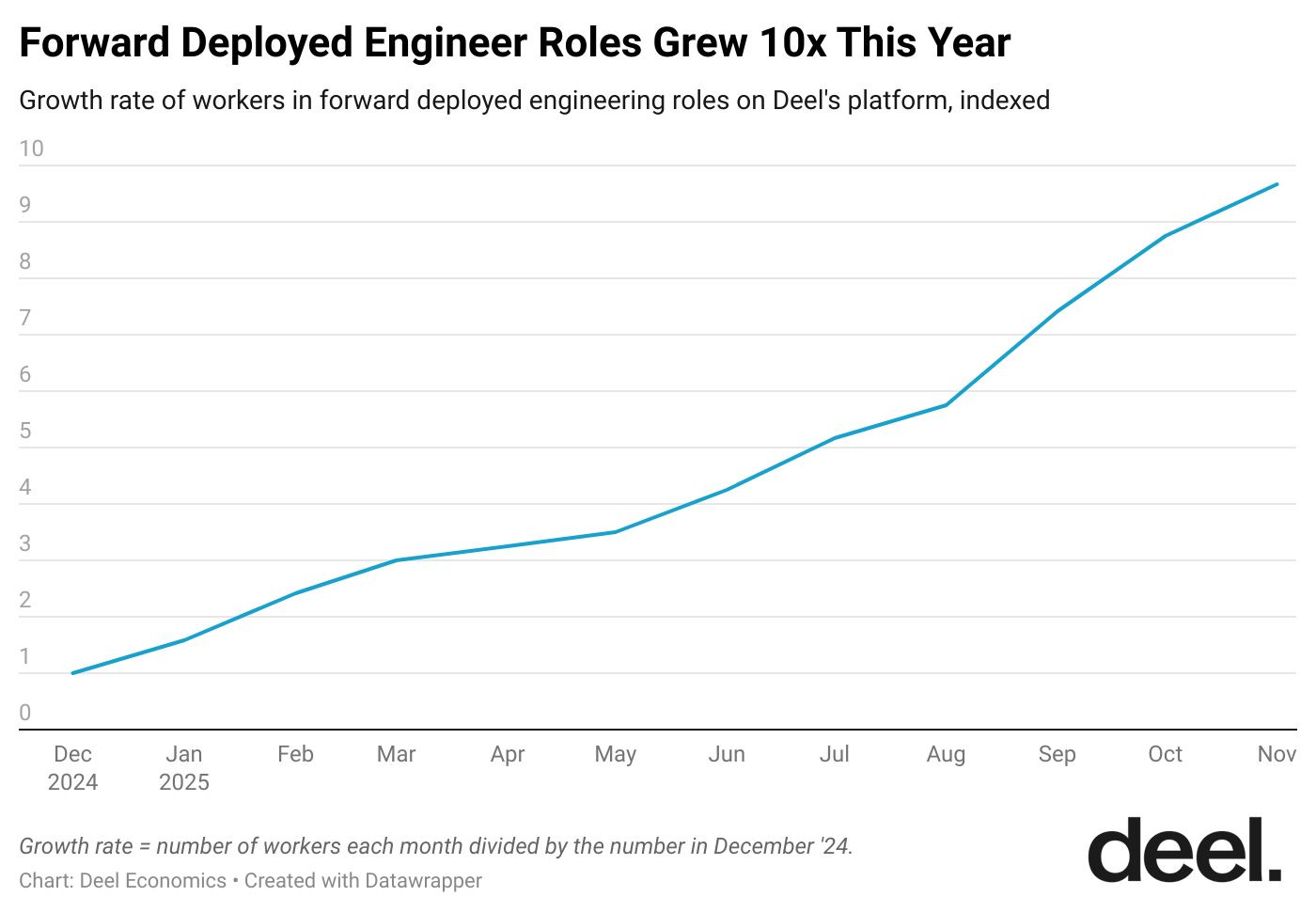

It is very much the job of the year. Here’s some data from Alex at Deel.

In a complex enterprise context, it makes a lot of sense having engineers embedded in the customer that can actually make your product work, or if you don’t quite yet have one, make it. This in part a reflection of the current immaturity of AI solutions, but also of the flexible potential of these solutions, and the promise and threat of disruption. We are told this is not consulting of old, but something far more powerful, and perhaps it is. There is a sales angle too, off course.

But many VCs and therefore VC funded companies are in danger of fetishising the FDE.

Also while I’m here, let’s all make a promise to stop quoting a poorly researched article from someone at MIT about 95% AI projects failing.

Two years ago or so, much of venture capital and the associated punditry insisted that all B2B products embrace product led growth, PLG. Software was supposed to deploy itself at a click of a button, and then incrementally monetise the customer as they use more features. The product manager was not only responsible for building solutions, they also needed to automate the GTM through the product too. We contorted things to fit PLG that should not been anywhere near it. I’ve been guilty of this.

Both are useful techniques, when applied in the correct context. They are dangerous when they become a fashion imperative. Much of VC saw PLG become the must have capability, irrespective of product requirements or customer size. This was nuts. But in the last year or so, talk of PLG has died to a whisper. This is also nuts.

Don’t assume that every product needs FDEs, or worse lots of them. If you are having to do complex technical work, where there is a lot of uncertainty in terms of scope, you are doing something that hasn’t been done before, and the contract value of what you have sold is significant, then an FDE is what the doctor ordered. For now.

But in the wrong context, and done wrong it is poor substitute for a well engineered, end-user-configurable product. It is relatively easy for an FDE centric software business to become indistinguishable from poorly managed software heavy consultancy. I’ve explored some of these dangers here.

Angular Ventures David Petersen is thinking on similar lines. Read his eloquent and thoughtful post here.

I always get nervous when a tactic gets sexy enough to become “the playbook.”

That is what happened to product-led growth in the late 2010s. And I suspect that is what is happening to “forward deployed engineers” in AI now.

Most AI startups do not live in that universe. If your median deal is $100K and you are copying the GTM of a company doing multi-million-dollar deployments to the DoD, you are probably telling yourself a nice story while you quietly build a consulting firm.

Have a deep listen to Ray and Dave on the Metrics brothers podcast They raise lots of questions about how to account for FDEs and then helpfully answer them.

I suspect a lot of the jobs labeled FDE today are either implementation or pre-sales roles with a cooler label, or worse at project based development company that thinks it is a product company. If the FDE is billable, they are working for the project, not the product. This could get messy.

As with many things product, Marty Cagan offers wisdom. He is a strong advocate of sending engineers to customers, as I am.

Product managers should not shut the gate between direct engineer and customer engagement. Getting engineers, designers and product manager all involved in product discovery is good practice.

I think though, there is a big difference between sending engineers to work with customers for a time, and placing them at the customer permanently.

Marty makes the point:

The challenge with this model in Palantir’s case is that if all they had were FDE’s, then they would quickly end up with thousands of large, bespoke solutions that would need to be maintained and improved indefinitely.

What makes Palantir so effective and so valuable is that they approached this problem as a platform product company.

Each FDE is building prototypes using the latest of their platform services, and the platform product organization is constantly working to generalize and incorporate the new capabilities being identified by the FDE’s into the continuously evolving and improving platform.

Platform product is about understanding how to synthesize what is being learned across many FDEs, or what FDEs heard across many clients, or both, and then identifying the buildable abstractions, and creating the product capabilities that will make similar work significantly faster for the next client.

In all the noise about FDEs we are at the risk of forgetting the difference between project and product. Next year’s cool job will be platform product manager.

About Sales

Selling late-stage enterprise SaaS is relatively formulaic, in that customers largely know how to buy it, and what they are looking for. Generally speaking, they can sniff when sales people are stretching the bounds of credibility. Sales people also know who can actually buy. When a product exists, and is relatively stable, injecting engineering folks to the sales cycle often is counterproductive. There are several Dilberts on this.

We are at the very early stage of genuinely AI centric solutions. We have had Potemkin AI for a while, but we are now in a period of significant turmoil. Welcome to massive misunderstandings between customer and sales. We are deep in perpendicular parallel lines territory.

Selling AI centric solutions requires a significant technically astute pre-sales capability. Firstly to convince the customer to do business with you, and secondly to sell something that is actually feasible (or to stop sales selling something that isn’t, which is a harder gig).

Back in time

I’m often guilty of reminiscing about previous eras of software, but tolerate me for a moment here. When SAP started, the engineers were forward deployed. Heck the development was even done on the customer’s mainframe. There’s nothing more forward than borrowing your customer’s computer. It was bleeding edge stuff, no-one had done accounting in real time before (The R in R/1, R/2 and R/3 meant realtime).

Over time SAP figured out how to take what they learnt at one or two customers, and make it work for many. As the customer base grew, and the product scope became clearer, it made sense to have consultants work with the customer, and built out a focused platform engineering function that collaborated with each other. Then big part of SAP’s success came through empowering the likes of IBM, Andersen Consulting and Price Waterhouse to to do the consulting work. Essentially they became part of the sales engine too.

As a founder today, you’ll learn more about enterprise software from the history of incumbents than from their current practices.

My first career job

In late 1991 Mark Stuckenberg, from QData, came around to WITS business school in Johannesburg where I was studying for the PGDip in HR, and he asked if any of us had computers or programmed a bit at home. A couple of us put up our hands and he quickly offered us jobs in HR Tech. My father was especially thrilled to see me move off his payroll into payroll.

After a bit of product and technical training, we were sent off as consultants to implement a product called HURQLES1. It was an HR system of sorts, competing with the likes of R/2 and Dun and Bradstreet. I didn’t know it at the time but I soon learnt the product was very much under development rather than the finished article (a common misapprehension for those new to the software industry). The product was written partly in COBOL, used a relational database model (DB2 and others), made extensive use of SQL, and had a proprietary scripting language for workflows. Data model-wise, not that much different from today’s SuccessFactors or Workday, but back then, this was all funky and new (except the COBOL bit).

My first project was in Cape Town at a major insurance company, far away from the Midrand head office. I found myself “coding” small but important elements of the product at night with the engineers over the phone, in order that we could deploy the feature the next day on the customer’s mainframe. I say coding but there was a lot of dictation involved, and swearing in Afrikaans. Nee fok Thomas jou doos etc.

I was the only vendor representative on the project, which was led by Andersen Consulting; I joined the project 18 months in, replacing a brilliant consultant (David Graham) who had 3 years of deep technical experience with the product code, on the same billing rate, after 2 months of training. I quickly became the forward deployed punchbag.

I still have nightmares about secondary selection rules, nestled query performance and job control language.

That project took me to Cape Town, which enabled me to date Charlotte, so all good in the end.

Looking forward

This is the most exciting time to be building enterprise software since the Lyons Tea Room project in 1951. Some of the product building assumptions we have held as gospel must remain gospel, others must be discarded. I’m all for rethinking the product development lifecycle.

We don’t yet know how to deploy AI at scale effectively in the enterprise, so the FDE is a useful component. But let’s account for it properly in the financial statements and understand its scaling limitations. Let’s not ignore modern product management while we are are at it. Building myopically at and for one customer is not a product, its a project. Let’s make sure we set the expectations correctly for customers, the FDEs and the product and platform teams.

For many companies, FDE will merely be marketing mechanism to attract technically astute people into services and presales work, the hype will drive up salaries for these roles but eventually may well leave those FDEs frustrated.

Empowering FDEs to make product, not merely project decisions will require a deeper rethink of the the product development lifecycle than we currently perceive. Traditional SaaS product management didn’t do a good job of listening to services, so there is lots to work on. I sense Palantir should be seen as an inspiration, rather than a rule or play book.

As an investor I’m going to ask you lots of awkward questions about FDE and PLG. I want to understand how you plan to build product, and get your first customers genuinely live. We aren’t funding consultancies though, I really want to know how you will take what you learn and build into something truly scalable. I’ll ask you how you reconcile the FDE work and the roadmap. How will you fund the FDEs and reflect it in your financials? How will you manage the tensions between the FDE who likes to build cool stuff for the customer, and automating those tasks, perhaps through PLG? I don’t have the answers, but I want to understand how you are thinking about it.

Rethinking services holistically with an example from our portfolio

The hype around FDE creates a welcome opportunity to rethink how services work in an AI centric company. There is goodness in making services cool again.

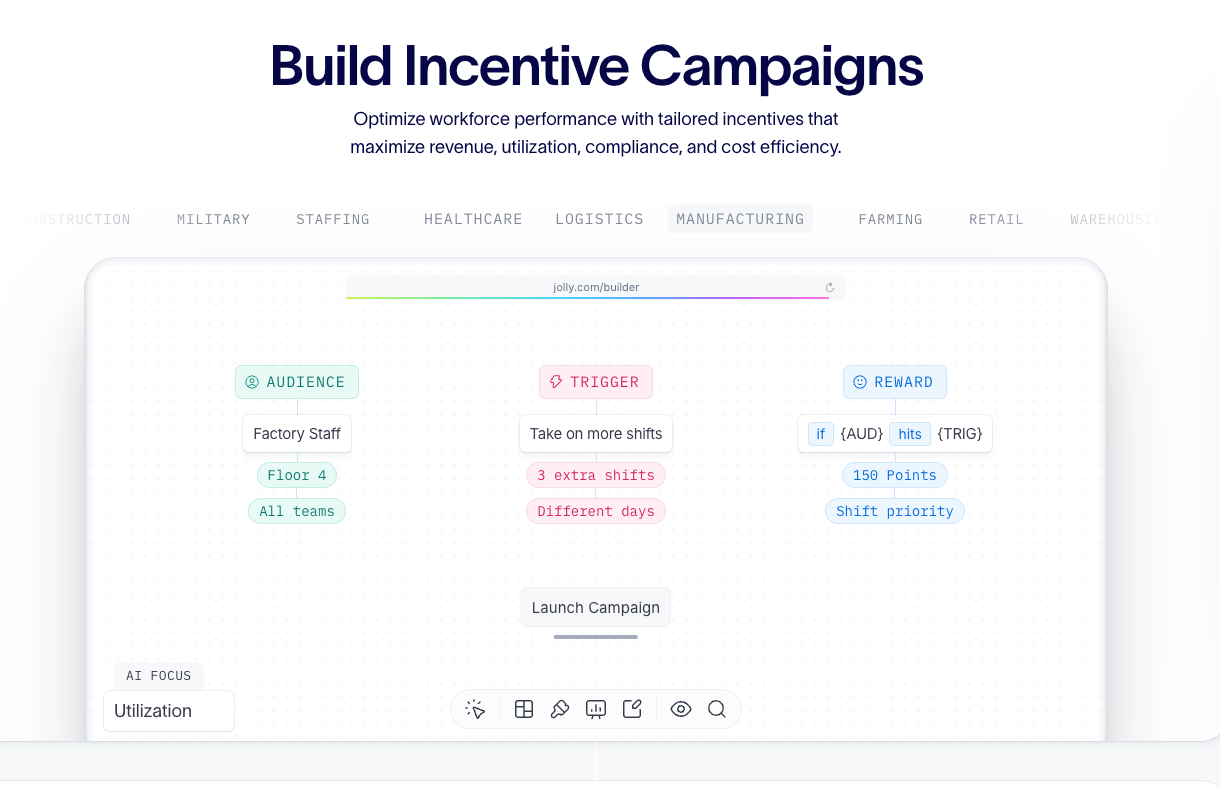

When you come with a novel idea, and a clever plan to drive adoption, I’ll be all ears. For instance, Dean at Jolly is rethinking employee incentive management. Dean spent some time at Palantir and Tesla before starting Jolly.

As part of better incentive management, he embeds what he is calling Incentive Engineers at their major clients. They will understand the customer’s business, drive adoption, advise clients, help a bit with configuration, prove value and more. Dean explains in a post here. I’ve stolen a chunk here, but follow him.

Whose job is it to design incentives at your company?

I asked that question to over 100 business leaders the past few weeks.

The answers:

“HR handles that”

“Our comp team… well, our comp analysts and HR, I think”

“Finance?”

“Isn’t that just part of management?”

Here’s the truth: It’s everyone’s job. Which means it’s no one’s job.

Incentive design typically spans HR, operations, and finance, with no single owner, creating misalignment and value leakage.

For incentive-obsessed companies, it’s always top of mind:

- Private equity firms spend hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars designing equity incentive plans for C-suite executives.

- Video game companies employ entire teams of behavioral psychologists to keep players engaged for hours.

- Starbucks has a loyalty team hyper-focused over how to get you to buy one more latte.

But who’s designing incentives that are actually EBITDA-generative and fun?

Usually, the answer is nobody.

That’s the problem we’re solving at Jolly. And it starts with a role that should exist at every company: the Incentive Engineer™

Have a look at the job description here.

Role Overview: Our Incentive Engineer role at Jolly is akin to an Engagement Manager role at a consulting firm, where you’ll be at the intersection of implementing board-level value creation initiatives, revenue operations, data analytics and client success. Your job will be to work with executives across a select group of clients to understand their key business initiatives that involve engineering behavior change across the frontline workforce (i.e. improving employee timeliness or maximizing new SKU sales) and leverage the Jolly platform to create new incentive campaigns that result in the desired behavior change.

In addition to understanding key initiatives, mapping them to the relevant data fields, and engineering the incentive campaigns, you will work closely with business executives to track and show how KPIs change as a result of Jolly rewards spend. You’ll own the creation of detailed ROI reports and go onsite with business executives frequently in order to continually understand and adapt Jolly’s incentive engineering to reflect current business initiatives.

The insight here is that for Jolly to be successful, it needs to drive meaningful change at the customer. The solution is a radical shift from how incentives have been done, so it will require careful engagement, especially at first. Configuring the software is straight-forward, but encouraging process and culture change isn’t.

What’s extra brilliant about the solution is that makes extensive use of PLG concepts such as sophisticated gamification to drive both employee and employer adoption and therefore monetisation. The business model is a mix of SaaS and outcome based.

Dean’s realised that it’s not an either/or between services and PLG, but that you can design solutions that create a virtuous circle. He’s taken what he has learnt at Palantir and applied it smartly to a different problem. More about Jolly below:

Ending this: gosh I’ve rambled on.

As VCs we tend to take good ideas and overcook them. FDE is no exception. Let’s use it judiciously.

I’ve another rant brewing about the contradictions between the promise of vibecoding and deification of the FDE, but that may or may not be a future post.

As usual, here’s a tune or two to round things off.

Did you spot the inspiration for the baggy suit image? Only David Byrne could pull this suit and dance off.

Also the background in the nano banana pic has a tenuous link to OMD. The cover of the OMD album Crush was inspired by an Edward Hopper Painting. Here’s a song from that album. In 1985 I thought OMD were fabulous. They still are.

Someday I will write up the early 1990s software industry in South Africa post. The constraints of sanctions had some unintended consequences.

Couldn't agree more. This shift to FDE deeply mirrors current AI solution immaturity.

"My father was especially thrilled to see me move off his payroll into payroll" nice phrasing. I enjoyed reading the writing.